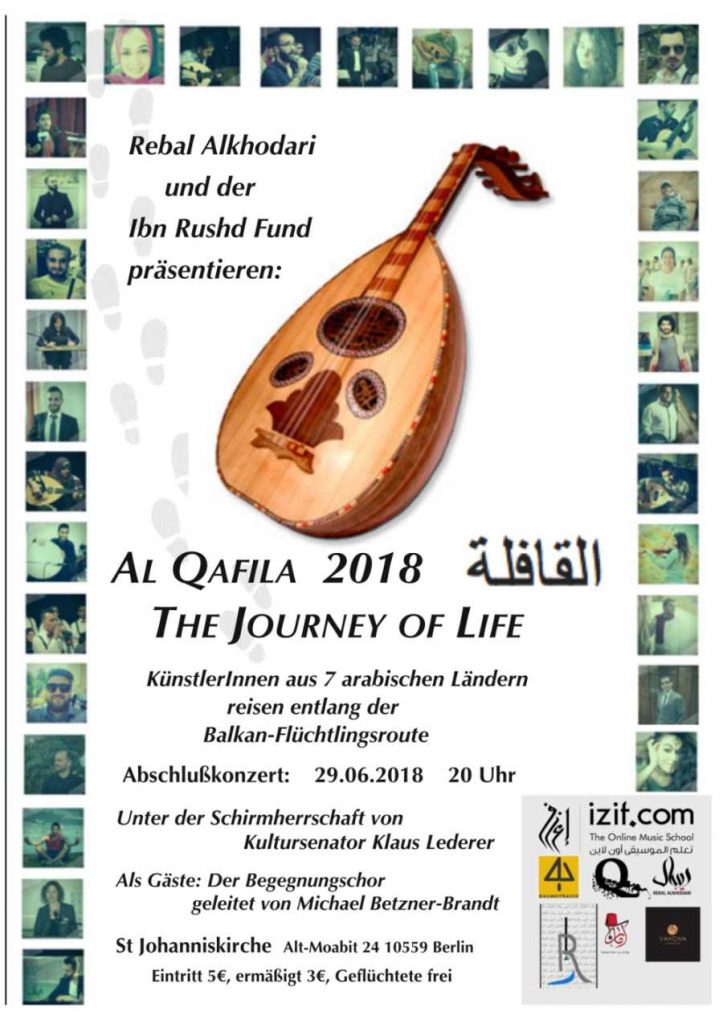

Ibn Rushd on tour with Al Qafila 2018 – the cultural caravan on the Journey of Life along the ‘Balkan Route’.

The Qafila al-Hayat sends artists and musicians from seven Arab countries on a Journey of Life to travel as a caravan in the footsteps of the men and women who fled war and destruction in their home countries in the Middle East along what became known as the Balkan Route.

And while they are experiencing their compatriots journey, these young people are on a mission: to show local audiences the rich culture that is a treasure brought by the people traveling towards a future on this most fateful journey of their lives.

As their artistic luggage, the qafilers are bringing their voices and musical instruments such as oud, kanun, violin, percussion and piano for the first part of the event Zyriab, named after the legendary musician of Andalusian times. With this sweet music still humming in their ears, listeners can proceed to be delighted by the second part of the event that’s displaying other samples of Arabic arts in a cultural market named after the famous Ukaz from pre-islamic times, on which poets competed and so, together, shaped the Arabic language.

On the Ukaz of the Al Qafila, there are traditional paintings and typical wood carvings on display and available, as well as samples of Arabic Spices like Baharat, Camun, Sumak and Hal – and the famous Ma’amoul, those cookies betraying their solid looks with a smell of roses and a date filling just as heavenly – and many more things.

Al Qafila, facts of past and present:

- 35 participants from 7 Arab countries: Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria – and some from their new homes in Germany, Iceland, and Canada.

- 13 women 22 men

- 16 singers 7 oud 2 kanun 1 violin 1 piano 1 percussion

- 1 market presenting traditional arts from Arabic regions – painting – handmade jewellery – traditional herbs – wood carving – culinary arts – sweets

Al Qafila, قافلة A qafila is a caravan: a group of people traveling together, often on a trade expedition. Historically, caravans were used mainly in desert areas and throughout the Silk Road, where traveling in groups aided in defense against bandits as well as helping to improve economies in trade. In historical times, caravans connecting East Asia and Europe often carried luxurious and lucrative goods, such as silks or jewelry.

Caravans could therefore require considerable investment and were a lucrative target for bandits. The profits from a successfully undertaken journey could be enormous, comparable to the later European spice trade. The luxurious goods brought by caravans attracted many rulers along important trade routes to construct caravanserais – roadside stations which supported the flow of commerce, information, and people across the network of trade routes covering Asia, North Africa, and southeastern Europe, especially along the Silk Road.

Caravanserais provided water for human and animal consumption, washing, and ritual ablutions. Sometimes they had elaborate baths. They also kept fodder for animals and had shops for travellers where they could acquire new supplies. In addition, some shops bought goods from the traveling merchants. However, the volume a caravan could transport was limited even by Classical or Medieval standards. For example, a caravan of 500 camels could only transport as much as a third or half of the goods carried by a regular Byzantine merchant sailing ship. Present-day caravans in less-developed areas of the world often still transport important goods through badly passable areas, such as seeds required for agriculture in arid regions. An example are the camel trains traversing the southern edges of the Sahara Desert.

Another very important version of a contemporary caravan is the Al Qafila transporting the cultural goods of exchange, communication, mutual understanding and respect brought into fashion by the Al Qafila project developed by the Syrian singer Rebal Alkhodari and Cora Josting from the Ibn Rushd Fund, and the indispensable team on the ground in the Middle East Muntasir Aladwan, Alaa Altaybe and Qasem Elhato, this year joined in Athens by the renown oud-player Tarek Al Jundi, who sends his special greetings through musical messengers to the caravanserais in Belgrade, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Munich and Berlin.

Al Qafila 2018 caravanserais along the Balkan Route in:

- Athens, 14-18 June Concert: June 18, 21h Al Qafila led by Rebal Alkhodari and Tareq al-Jundi guest: Martha Frinzila Baumstrasse Center, Servion 8, 10441 Athens

- Thessaloniki, 19 June

- Belgrade, 20+21 June Concert: June 21, 19h – Al Qafila led by Rebal Alkhodari CZKD, Paviljon Veljković, Birčaninova 21, 11000 Belgrade

- Zagreb, 22+23 June June 23, 18h Al Qafilers walk through Zagreb with the Danish artist in residence Maj Horn, Zagreb local artists, refugees and residents of Zagreb; followed by a concert-picnic at 20h in Park Tuškanac with music provided by singers + musicians of Qafila al-Hayat, led by Rebal Alkhodari, and a picnic prepared by Qafila al-Hayat’s Arabic chefs and the Kolektiv Sjemenčice at Zelena Akcija kitchen; all organized in collaboration with Lab852 art agency

- Ljubljana, 24+25 June Musical interventions in the old city

- Munich, 26 June Musical interventions in the old city

- Berlin, 27 June to July 3 Concert: June 29, 20h Under the patronage of Cultural Senator Klaus Lederer Al Qafila led by Rebal Alkhodari Guest choir: Begegnungschor led by Michael Betzner-Brandt St Johanniskirche, Alt Moabit 25, 10559 Berlin

Ziryab, زرياب literally means ‘Blackbird’.

The artist was well-known for his black skin and versatile tongue, which inspried his nickname. This universal artist lived in Iraq, Northern Africa and Andalusia from 789-857 and was a singer, oud player, composer, and teacher knowledgeable in astronomy, geograühy, meteorology, botanics, cometics, fashion and culinary art, and a father of ten. He came to fame at the court of Abd ar-Rahman II of the Umayyad Dynasty. Abd ar-Rahman II was a great patron of the arts and Ziryab was given both a generous living and a great deal of freedom which he used to revolutionize the court at Córdoba and make it the stylistic capital of its time. Whether introducing new clothes, styles, food, fashion, hygiene products, or music, Ziryab changed al-Andalusian culture forever. The musical contributions of Ziryab alone are staggering – he is said to have improved the oud by adding a fifth pair of strings and using an eagle’s beak instead of a wooden pick, and established one of the first schools of Music in Córdoba that was open to both male and female students – laying also the early groundwork for classic Spanish music. Ziryab transcended music and style and became a revolutionary cultural figure in 8th and 9th century Iberia. (abbreviated version of entry in Wikipedia)

‘Ukāz, عكاظ Marketplace and site of fairs and poetry contests in Mecca from 4-7 century.

The time it took place was tied to the pilgrimage season in pre-Islamic times and the location served as a place where warring tribes could come together peacefully to worship and trade together. It was abolished by Mohammed but a similar practice was established during the Haj. For those who’d like to know more, the Dictionary of Islam by Thomas P. Hughes, first published in London in 1885, quotes a Mr Stanley Lane Poole, who is quoted below with his description of the market that is much more eloquent and elaborate than our short explanation based on Wikipedia. There was one place where, above all others, the Kaşeedehs (Qaşīdahs) of the ancient Arabs were recited: this was the ‘Okádh (‘Ukāz), the Olympia of Arabia, where there was held a great annual fair, to which not merely the merchants of Mekka and the south, but the poet-heroes of all the land resorted. The fair of the ‘Okádh was held during the sacred months, – a sort of ‘God’s Truce’, when blood could not be shed without a violation of the ancient customs and faiths of the Bedawees. Thither went the poets of rival clans, who had as often locked spears as hurled rhythmical curses. There was little fear of a bloody ending to the poetic contest, for those heroes who might meet there with enemies or blood-avengers are said to have worn masks or veils, and their poems were recited by a puclic orator at their dictation. That these precautions and the sacredness of the time could not always prevent the ill-feeling evoked by the pointed personalities of rival singers leading to a fray and bloodshed is proved by recorded instances; but such results were uncommon, and as a rule the customs of the time and place were respected. In spite of occasional broils on the spot, and the lasting feuds which these poetic contests must have excited, the fair of ‘Okádh was a grand institution. It served as a focus for the literature of all Arabia: everyone with any pretensions of poetic power came, and if he could not himself gain the applause of the assembled people, at least he could form one of the critical audience on whose verdict rested the fame or shame of every poet. The Fair of ‘Okádh was a literary congress, without formal judges, but with unbounded influence. It was there that the polished heroes of the desert determined points of grammar and prosody; here the seven Golden Songs were recited, although (alas for the charming legend!) they were not afterwards ‘suspended’ on the Kaabeh; and here ‘a magical language, the language of the Hijáz’, was built out of the dialects of Arabia, […]. “The fair of the ‘Okádh was not merely a centre of emulation for Arab poets: it was also an annual review of Bedawee virtues. it was there that the Arab nation once-a-year inspected itself, so to say, and brought forth and criticized its ideals of the noble and the beautiful in life and in poetry. […]